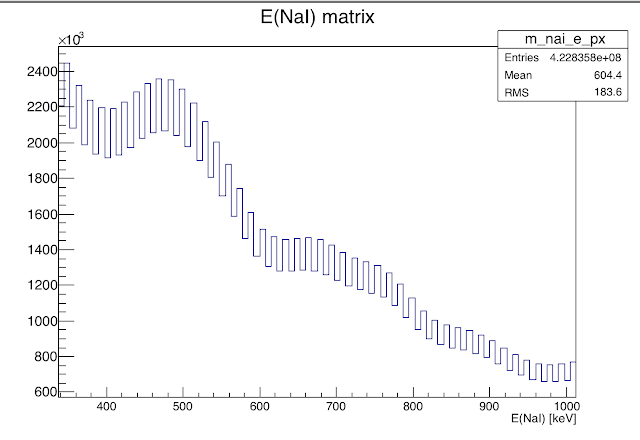

Why is the nuclear sweat from fission always the same?

One small step…

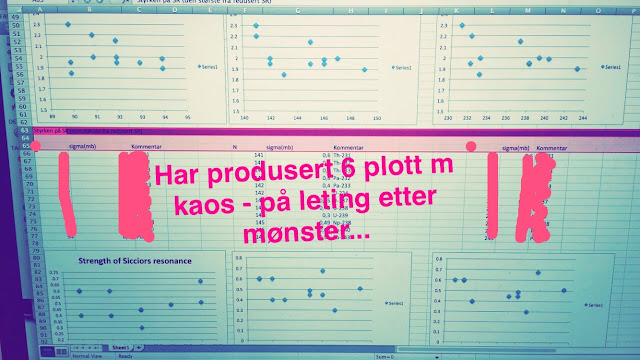

Six plots (#phdlife)

It's getting real…

My kind of poetry…

Forskningen er internasjonal! (rant)

Study of the 238U(d,p) surrogate reaction via the simultaneous measurement ofgamma-decay and fission probabilities (5 norske forfattere - vi kunne ikke ha vært med på denne hvis den ble skrevet på hovedforfatteren sitt morsmål, men heldigvis publiserer de på engelsk også i Frankrike)

Experimental level densities of atomic nuclei (16 forfattere som ikke forstår norsk - som ikke kunne ha bidratt til det endelige resultatet). Denne er jo til og med nesten populær i sin fremstilling. Abstractet lyder:

It is almost 80 years since Hans Bethe described the level density as a non-interacting gas of protons and neutrons. In all these years, experimental data were interpreted within this picture of a fermionic gas. However, the renewed interest of measuring level density using various techniques calls for a revision of this description. In particular, the wealth of nuclear level densities measured with the Oslo method favors the constant-temperature level density over the Fermi-gas picture. From the basis of experimental data, we demonstrate that nuclei exhibit a constant-temperature level density behavior for all mass regions and at least up to the neutron threshold.

La meg være litt grei, og gjøre en rask oversettelse av dette abstractet:

Det er nesten 80 år siden Hans Bethe beskrev nivåtettheten som en ikke-vekselvirkende gass av protoner og nøytroner. Siden da har alle eksperimentelle data blitt tolket i dette bildet av en fermion-gass. Dog har den fornyede interessen for å måle nivåtettheten ved å bruke forskjellige teknikker gjort at denne beskrivelsen må revurderes. Spesielt så favoriserer det vellet av nivåtettheter målt med Oslometoden konstant temperatur-nivåtettheten fremfor fermigass-bildet. Med bakgrunn i eksperimentelle data de

monstrerer vi her at kjerner viser en konstant temperatur-nivåtetthetsoppførsel i alle masseregioner, og i alle fall opp til nøytron-bindingsenergien.

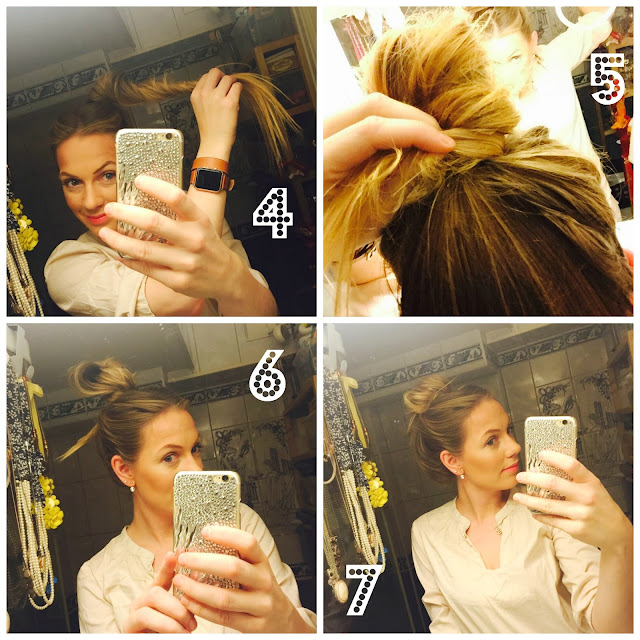

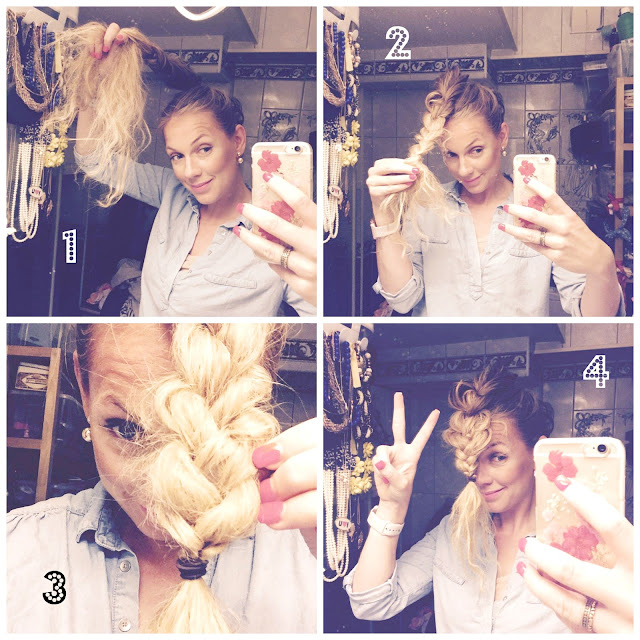

Working your ass off – hairdos

1. messy bun

2. messy braid no 1

3. messy braid no 2

The messy bun and the messy braid number 1 and 2 start with the same messy pony tail (steps 1-3):

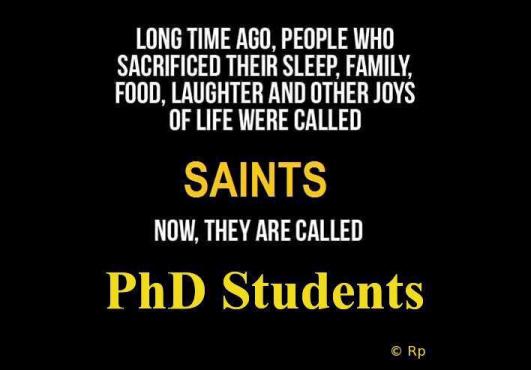

10 facts about getting a PhD

- After you get a master's degree, you can continue with a PhD

- The actual PhD work is 3 years, but many of us also have 25% teaching so that we have the job for 4 years in total (the teaching is normally done during the time you also work on the degree)

- To be admitted to the PhD program at the University of Oslo, you have to have quite good grades; B as an average on the courses in your master's degree, and at least B on your master thesis

- Most of the PhD degree is research, but you also have to take one semester (in total) with courses (one of the courses is a mandatory ethics course - which sounds like a good idea, but when I took the course, I thought it wasn't a particularly good course...:/ )

- My courses were the ethics course, one called "Communicating Scientific Research", a statistics course (STK9900), and a nuclear structure course ("advanced nuclear structure and reactions")

- The main part of the PhD is research; you have to do stuff that is new, and the results must be of such a quality that it's published in serious, peer reviewed joournals (if your work isn't worthy publishing, well, then that's too bad for you - no PhD!)

- The actual "thesis" is a collection of the articles you write (often it's something like three), and an "introduction" where you sort of sow everything together (which can be challenging when you feel like your articles have almost nothing in common), and write in detail about the methods you've used, and experimental setup, and theory and stuff (for example, I write about nuclear power in general, nuclear reactions that are interesting and important for nuclear reactors, simulations of nuclear fuel, and the Oslo Cyclotron Laboratory, and of course there is some kind of conclusion after the articles 🙂 )

- When everything is finished (your research, your article writing, your thesis writing, and your funding), the entire thing will be sent to a committee (experts in the field, of course 😉 ) that will read everything carefully and decide whether the thesis is worthy of defending, or not. (If they decide it's not at all worthy, you don't get a chance to make it better, and all your work is worthless for the degree - if still you want to get a PhD then, you have to start ALL.OVER.AGAIN.)

- After the committee says the thesis is ok, you'll get the date for the thesis defence, and two weeks before this, you get the title of you trial lecture that you have to prepare for the thesis defence. This could be almost anything (is my impression), but it's normally related to your research

- The last part is the day of the thesis defence: it starts with the trial lecture, and if this is approved, then you get to actually defend your thesis. The defence happens later the same day; first you give a short presentation of the work, and the two opponents will ask all kinds of questions about it and discuss with you. After they've finished, people in the audience can ask questions. All of this is public. At the end of the day, after the committee (hopefully) approves of your work, you have to have a dinner with the opponents and your supervisor, and maybe your friends and family <3